Did Theranos Actually Invent Anything? The Real Story Behind The Claims

The story of Theranos and its founder, Elizabeth Holmes, has truly captivated many people. It's a tale that seems to come straight out of a movie, full of grand promises, incredible wealth, and a dramatic downfall. For years, the company claimed it was going to change healthcare forever, making blood testing simpler and more accessible for everyone. This vision, so it was said, rested on some truly groundbreaking technology.

Many folks, you know, bought into this big dream. The idea was that Theranos had figured out how to run a huge number of blood tests from just a few drops of blood, all using a tiny machine. This sounded like a huge step forward, especially for people who might be a bit nervous about needles or who needed frequent testing. It seemed like a genuine miracle for the medical field, and many investors and the public were very excited, to say the least.

But as time went on, a lot of questions began to surface. People started wondering if these amazing claims were actually true. Was the technology really working as promised? Or was there something else going on? This very question, "Did Theranos actually invent anything?" became central to the whole saga, and its answer really tells us a lot about what went wrong, you know, with the company.

Table of Contents

- The Grand Vision: What Theranos Claimed

- The Machines of Myth and Reality

- The Truth Unraveled: What Really Happened

- The Question of Innovation and Fraud

- Impact and Lessons Learned

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Conclusion

The Grand Vision: What Theranos Claimed

Theranos, as a company, really spun a compelling story. They told everyone they had invented a revolutionary blood-testing system. This system, they said, could perform hundreds of different tests, from cholesterol levels to cancer markers, all from just a tiny prick on your finger. It was supposed to be faster, cheaper, and more convenient than traditional lab methods, which typically need bigger blood draws and more complex equipment. That, you know, was the big promise.

Elizabeth Holmes, the founder, was very good at presenting this vision. She spoke about making healthcare more democratic, giving people more control over their own health information. She often talked about how her technology would help detect diseases earlier, allowing for quicker treatment and better outcomes. It sounded like a truly noble goal, and it certainly captured the imagination of many, including powerful figures and investors, so it's almost understandable why people believed her.

The core of their claim rested on their proprietary devices, particularly one they called the "Edison." This machine, they suggested, was a compact, automated laboratory in a box. It would be placed in pharmacies and wellness centers, allowing anyone to walk in, get a quick finger-prick blood test, and receive comprehensive results almost immediately. This was, frankly, a pretty bold claim, especially considering the existing technology at the time.

They also hinted at other innovations, like a tiny patch that could continuously monitor health markers. The company's marketing and public relations were very strong, creating an image of a cutting-edge tech company that was poised to disrupt a slow-moving industry. They were, in some respects, masters of storytelling, even if the underlying technology wasn't quite there yet, or ever, as it turned out.

This grand vision attracted billions of dollars in investment, making Theranos one of the most valuable private companies at its peak. It also made Elizabeth Holmes a very young billionaire, and she became a media darling, often compared to tech titans like Steve Jobs. The belief in her and her company's supposed inventions was, you know, truly widespread, and it fueled their rise for quite a while.

The Machines of Myth and Reality

So, what about these supposed inventions? Did Theranos actually have working machines that could do all these amazing things? This is where the story takes a turn, as a matter of fact, from grand claims to a very different reality. The company showcased two main devices: the "Edison" and later, the "miniLab." Both were presented as revolutionary, but their actual capabilities were, well, a bit different from what was advertised.

The Edison Device

The Edison machine was Theranos's flagship device, the one that Elizabeth Holmes talked about the most. It was supposed to be a small, automated system that could run a full panel of blood tests using only a tiny sample from a finger prick. The idea was that it would be simple to use, giving quick and accurate results, and that it would fit almost anywhere. This was, you know, the central piece of their supposed invention.

However, the truth about the Edison was far from the public image. Insiders and later investigations revealed that the Edison machine had serious limitations. It was prone to errors, often failed to produce reliable results, and could only run a very limited number of tests, not the hundreds Theranos claimed. Apparently, it was a very unreliable piece of equipment, and it just didn't work as advertised.

Instead of using their own Edison machines for the vast majority of tests, Theranos secretly relied on commercially available, traditional blood-testing machines from other manufacturers. They would take the tiny finger-prick samples, dilute them, and then run them on these standard machines, which were never designed for such small, diluted samples. This practice, in fact, compromised the accuracy of the results, and it was a huge part of the deception, basically.

The Edison, in essence, was more of a prop than a functional invention. It was shown off to investors and the public to create an illusion of advanced technology that simply didn't exist in a reliable form. The company spent a lot of time and money on its appearance, but very little on making it actually work consistently and accurately, which is, you know, a pretty big problem when you're dealing with people's health.

Many former employees spoke out about the Edison's failures, describing how they were pressured to hide its shortcomings and how the company actively misled regulators and partners about its capabilities. So, in short, the Edison was not the groundbreaking invention it was made out to be; it was, more or less, a non-functional prototype used to perpetuate a fraud.

The miniLab System

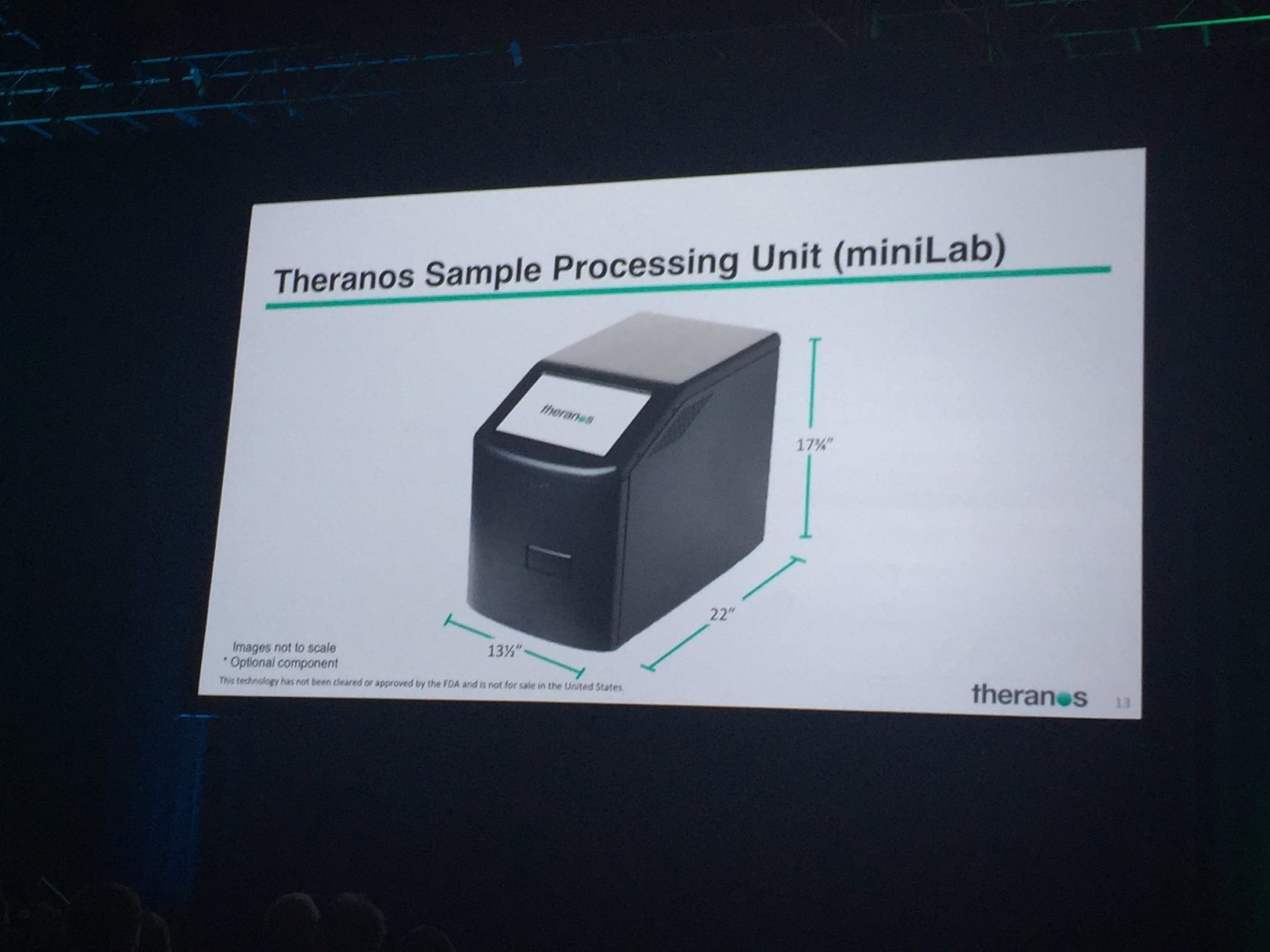

Later in its history, as scrutiny grew, Theranos tried to pivot and introduce another device called the "miniLab." This was presented as a more advanced, more reliable version of their technology. It was still supposed to work with small blood samples and automate the testing process. The miniLab was their attempt to show that they were still innovating and had something real to offer, you know, to the market.

While the miniLab might have been a step up from the Edison in some ways, it still fell far short of Theranos's claims and the expectations they had set. It was also never fully developed or proven to be reliable for widespread clinical use. The company continued to face the same fundamental problems: their technology simply wasn't able to perform the range and accuracy of tests needed for real-world medical diagnostics, as a matter of fact.

The miniLab, like the Edison, was largely a concept that never fully materialized into a functional, validated product. It was used, perhaps, to buy more time and to continue the illusion of progress, but it didn't solve the core issues of their technology. The company was still relying on traditional machines for most of its testing, and the results from those tests were often questionable due to their methods, which is, you know, a very serious issue for patient care.

The development of the miniLab also highlights a pattern within Theranos: a tendency to overpromise and underdeliver, to focus on marketing and fundraising rather than genuine scientific and technological breakthroughs. They were, in a way, always chasing the next big announcement rather than solidifying what they had. This pattern, arguably, sealed their fate, and it's a pretty clear sign of what was going on.

So, when people ask if Theranos invented anything, the answer regarding the miniLab is similar to the Edison: they conceptualized and built prototypes, but they never created a functional, reliable, and scientifically validated blood-testing device that lived up to their public statements. They had ideas and designs, but not working inventions that could actually deliver on their promises, basically.

The Truth Unraveled: What Really Happened

The unraveling of Theranos's claims began with investigative journalism and the brave actions of whistleblowers. John Carreyrou, a reporter for The Wall Street Journal, started publishing articles in 2015 that exposed the deep flaws in Theranos's technology and operations. He spoke with former employees who revealed that the company was not using its proprietary machines for most tests and that the results from the ones they did use were often inaccurate, you know, to say the least.

These revelations sent shockwaves through the tech and healthcare industries. Regulators, including the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), began their own investigations. What they found confirmed many of the journalist's reports: Theranos's labs had serious deficiencies, and their testing methods were not up to standard. This was, as a matter of fact, a huge problem for a company dealing with health data.

The company faced sanctions, including the voiding of thousands of test results and a ban on Elizabeth Holmes operating a blood-testing lab for two years. This pretty much crippled their ability to conduct business. The partnerships they had formed with major retailers like Walgreens and Safeway quickly dissolved, as these companies realized they had been misled, which is, you know, a pretty bad situation for everyone involved.

Eventually, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) charged Elizabeth Holmes and her former COO, Ramesh "Sunny" Balwani, with massive fraud. They were accused of deceiving investors by making false and misleading statements about the company's technology, business, and financial performance. This was a very serious accusation, and it showed the true extent of the deception, basically.

The legal proceedings that followed were lengthy and highly publicized. Both Holmes and Balwani were found guilty on multiple counts of fraud. Holmes received a sentence of over 11 years in prison, and Balwani received nearly 13 years. These outcomes truly cemented the fact that Theranos's claims were not just ambitious but were, in fact, part of a criminal enterprise designed to mislead investors and the public, so it's a very clear message about what happened.

The fall of Theranos serves as a stark reminder that even the most compelling stories and charismatic leaders need to be backed by actual, working technology and transparent practices. The truth, you know, eventually comes out, and in this case, it led to the complete collapse of a company that once promised to change the world, but instead, left a trail of deception and legal consequences.

The Question of Innovation and Fraud

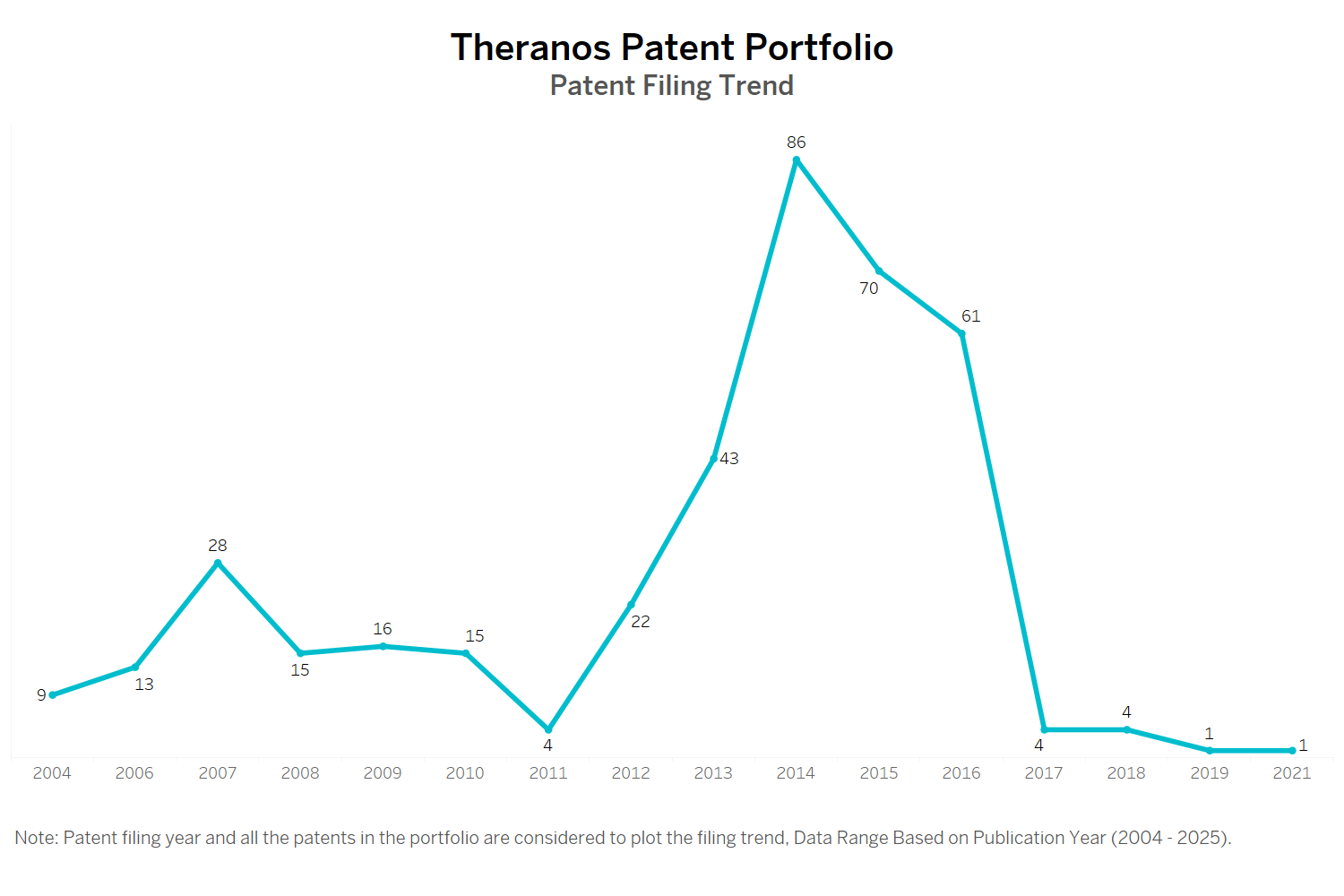

When we ask, "Did Theranos actually invent anything?", the answer is complex but leans heavily towards "no" in the meaningful sense. They certainly had ideas, and they built prototypes of machines like the Edison and miniLab. They also filed patents related to their concepts. However, having an idea or a prototype is very different from inventing a functional, reliable, and validated technology that works as claimed, which is, you know, the crucial distinction here.

True invention, especially in a critical field like healthcare, requires rigorous scientific validation, peer review, and proven accuracy. Theranos consistently bypassed these essential steps. They presented aspirational concepts as fully realized products, and they actively concealed the fact that their machines were not performing as promised. This behavior moved their actions from ambitious innovation into the realm of outright fraud, as a matter of fact.

The fraud wasn't just about exaggerating capabilities; it was about knowingly misrepresenting the core functionality of their technology and the state of their business. They used traditional machines in secret, manipulated data, and misled partners and investors about the very essence of what they were selling. This level of deception goes far beyond typical startup hype, basically.

So, while Theranos did engage in some research and development, and they did create physical devices, these devices never achieved the breakthrough capabilities that were so widely advertised. They did not invent a reliable, miniature blood-testing system that could perform a wide array of tests from a few drops of blood. That, you know, is the simple truth of it all.

The company's story highlights the difference between genuine scientific progress and a well-orchestrated marketing campaign. It shows how easy it can be to confuse the two, especially when there's a charismatic leader and a seemingly revolutionary idea involved. In the end, the lack of real invention at Theranos was a central piece of the fraud that ultimately led to its downfall, and it's a very important lesson for everyone.

Impact and Lessons Learned

The Theranos saga had a pretty significant impact, not just on the people directly involved but also on the broader landscape of innovation and investment. For one, it caused a lot of financial loss for investors who poured billions into the company based on false pretenses. Many reputable individuals and organizations lost a lot of money, which is, you know, a very unfortunate outcome.

More importantly, it eroded trust in the startup world, particularly in the health technology sector. It made investors and the public more skeptical of grand claims and forced a closer look at the due diligence process for new companies. People started asking tougher questions about scientific validation and regulatory oversight, which is, arguably, a good thing in the long run, as a matter of fact.

The case also brought attention to the importance of whistleblowers and investigative journalism in uncovering corporate misconduct. Without the courage of former employees who spoke out and the persistence of reporters, the truth about Theranos might have remained hidden for much longer. This shows how crucial independent scrutiny is, you know, for holding powerful entities accountable.

For the healthcare industry, the Theranos story serves as a cautionary tale about the need for rigorous scientific standards and regulatory compliance. Innovation is certainly vital, but it must be built on a foundation of accuracy, safety, and proven efficacy, especially when it comes to people's health. There's no room for shortcuts or deception when lives are at stake, basically.

Finally, the Theranos story reminds us all to approach seemingly miraculous claims with a healthy dose of skepticism. If something sounds too good to be true, it often is. It encourages us to look beyond the hype and ask for concrete evidence and validation, which is, you know, a very valuable lesson for anyone navigating new technologies and promises. Learn more about on our site, and also check out this page for related insights.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the Edison machine supposed to do?

The Edison machine was supposed to be a small, automated device that could perform a wide range of blood tests from just a few drops of blood, typically collected from a finger prick. Theranos claimed it would provide quick, accurate results, making blood testing much more convenient and accessible for everyone, so it was a very ambitious promise.

Did Theranos ever get FDA approval for anything?

Theranos did receive one FDA clearance, not a full approval, for a single test: a herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) test, in 2015. However, this clearance was for a specific test on a specific device, and it was a very limited scope compared to the hundreds of tests they claimed their technology could perform. It was, you know, a tiny piece of what they said they could do.

What happened to Theranos's technology?

Theranos's core technology, the Edison and miniLab devices, ultimately proved to be non-functional for their stated purposes. The company ceased operations in 2018, and its intellectual property, including any patents or designs for these machines, was likely dissolved or sold off during the liquidation process. The technology, as a matter of fact, never delivered on its promises and essentially faded away.

Conclusion

So, did Theranos actually invent anything truly revolutionary that worked as claimed? The overwhelming evidence points to a clear "no." While they had concepts and prototypes, they never developed a functional, reliable blood-testing device that lived up to their public statements. The story serves as a powerful reminder about the critical importance of truth and integrity in innovation, you know, for all of us.

Theranos Patents - Insights & Stats (Updated 2025)

Theranos documentary review: The Inventor’s horrifying optimism

The Tragic Design and Marketing of Theranos | Design is within the fibers.